WESTERN SAHARA CONFLICT

What is the Western Sahara Conflict?

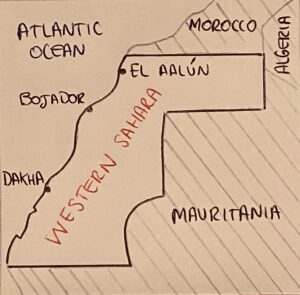

Western Sahara is a region located in the northeast of Africa and it is contested by Morocco and the Polisario Front, a Saharawi national liberation movement. After years of conflict and instability, its status remains an unresolved problem. Although in 1963 the area was recognised by the United Nations as a non-self-governing Territory, Spain occupied the region until 1975, when the United Nations General Assembly called for its decolonization. After the Green March, a mass demonstration organised by the Moroccan Government, Spain was forced to leave the colony and the administration of the area was given to Morocco and Mauritania: a war between the occupiers and the Saharawi Polisario Front broke out. In 1979, backed up by Algeria, the Saharawi nationalist movement proclaimed the region to be the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic. Due to the guerrilla warfare, Mauritania abandoned its sovereignty, leaving the Moroccans and the Polisario Front in control of Western Sahara.

Western Sahara is a region located in the northeast of Africa and it is contested by Morocco and the Polisario Front, a Saharawi national liberation movement. After years of conflict and instability, its status remains an unresolved problem. Although in 1963 the area was recognised by the United Nations as a non-self-governing Territory, Spain occupied the region until 1975, when the United Nations General Assembly called for its decolonization. After the Green March, a mass demonstration organised by the Moroccan Government, Spain was forced to leave the colony and the administration of the area was given to Morocco and Mauritania: a war between the occupiers and the Saharawi Polisario Front broke out. In 1979, backed up by Algeria, the Saharawi nationalist movement proclaimed the region to be the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic. Due to the guerrilla warfare, Mauritania abandoned its sovereignty, leaving the Moroccans and the Polisario Front in control of Western Sahara.

Could a referendum be the solution?

In 1992, the UN decided to organise a referendum with which the local population would decide whether they wanted to become independent or be annexed to Morocco. However, the motion did not come to fruition as Morocco observed that the referendum could not be carried out given the absence of a formalised list of the people who are authorised to vote. The Polisario Front claimed that the Spanish Census of 1974 could be used for the referendum, but Morocco did not agree with the decision as it believed that the list had been compromised. In 2000 the Baker Plan was discussed, and according to it all the people who are in the Saharawi territory should have the right to vote: as it was considered particularly in favour of Morocco, it was rejected. In 2003 a second more accurate version of the Plan was published. The Polisario Front declared its support but Morocco opposed it and is unwilling to hand over its power on the region.

In 1992, the UN decided to organise a referendum with which the local population would decide whether they wanted to become independent or be annexed to Morocco. However, the motion did not come to fruition as Morocco observed that the referendum could not be carried out given the absence of a formalised list of the people who are authorised to vote. The Polisario Front claimed that the Spanish Census of 1974 could be used for the referendum, but Morocco did not agree with the decision as it believed that the list had been compromised. In 2000 the Baker Plan was discussed, and according to it all the people who are in the Saharawi territory should have the right to vote: as it was considered particularly in favour of Morocco, it was rejected. In 2003 a second more accurate version of the Plan was published. The Polisario Front declared its support but Morocco opposed it and is unwilling to hand over its power on the region.

The Wall of Shame

The region is split not only due to supremacy reasons: a 2,720-kilometre-long wall divides it into the Moroccan and the Polisario Front areas. It is the second world longest wall and the military zone with the world longest minefield. Built over six phases, its construction began in 1980 from a small area close to Morocco, and then it reached the majority of the region. According to the Moroccan government, the aim of the wall is to defend the region from conflicts, while the Saharawi population believes that is it used to control the area and the economic interests of phosphate miners and oil fields.

Gdeim Izik protest camp and its consequences

In October 2010, in Laayoune, the Gdeim Izik protest camp was created with the aim of expressing disapproval and fighting against the unfair conditions in which the local Saharawi population lives. A few hundred tents became thousands: even though the protest was quiet at first, the situation escalated quickly resulting in conflicts between the Saharawi and Morocco. The protests lasted only a month, when the Moroccan police forces tore the camp down, putting Algeria on trial as they believed it had created and financed the protests in order to cause havoc. In 2016, the European Union declared that Western Sahara was not part of the Moroccan territory. However, to date, the majority of the region is controlled by the Moroccan Government and the rest of the territory is controlled by the Polisario Front.

Right to an identity

While the responsibles for the Western Sahara Conflict are many, the local population is the only victim. Decisions must be made in their interest, leaving aside the economic and imperialist ones. Western Sahara and Equatorial Guinea are the only Spanish-speaking African countries: their identity and cultural heritage might be lost forever. It is about time Saharawi have their rights defended and their dignity restored. The process needs to be more transparent and democratic, and it is necessary to find solutions that are acceptable and compatible with international standards and human rights. The voices of local women and men must be heard.

While the responsibles for the Western Sahara Conflict are many, the local population is the only victim. Decisions must be made in their interest, leaving aside the economic and imperialist ones. Western Sahara and Equatorial Guinea are the only Spanish-speaking African countries: their identity and cultural heritage might be lost forever. It is about time Saharawi have their rights defended and their dignity restored. The process needs to be more transparent and democratic, and it is necessary to find solutions that are acceptable and compatible with international standards and human rights. The voices of local women and men must be heard.